News that Eastern European countries are lining up for bailouts from the EU and the IMF is seen as part of the bursting of the credit bubble, but the event contains important lessons for South Africa as it ventures back into the offshore debt market. The current Eastern European economic crisis is due to the high level of offshore borrowing, which is threatening to bankrupt the region now that the their currencies have weakened.

What is surprising is that Eastern Europe failed to learn the recent lessons of East Asia (1997), Brazil (1998/9) and Turkey (2000/2001), as well as countless episodes in history where large amounts of foreign borrowing precipitated a currency and economic crisis. These countries learnt a harsh lesson as they ended up beholden to foreign borrowers in developed countries, or international organisations such as the IMF. The steps taken to reduce currency risk by countries that had previously experienced crises meant that they fared much better in the recent downturn.

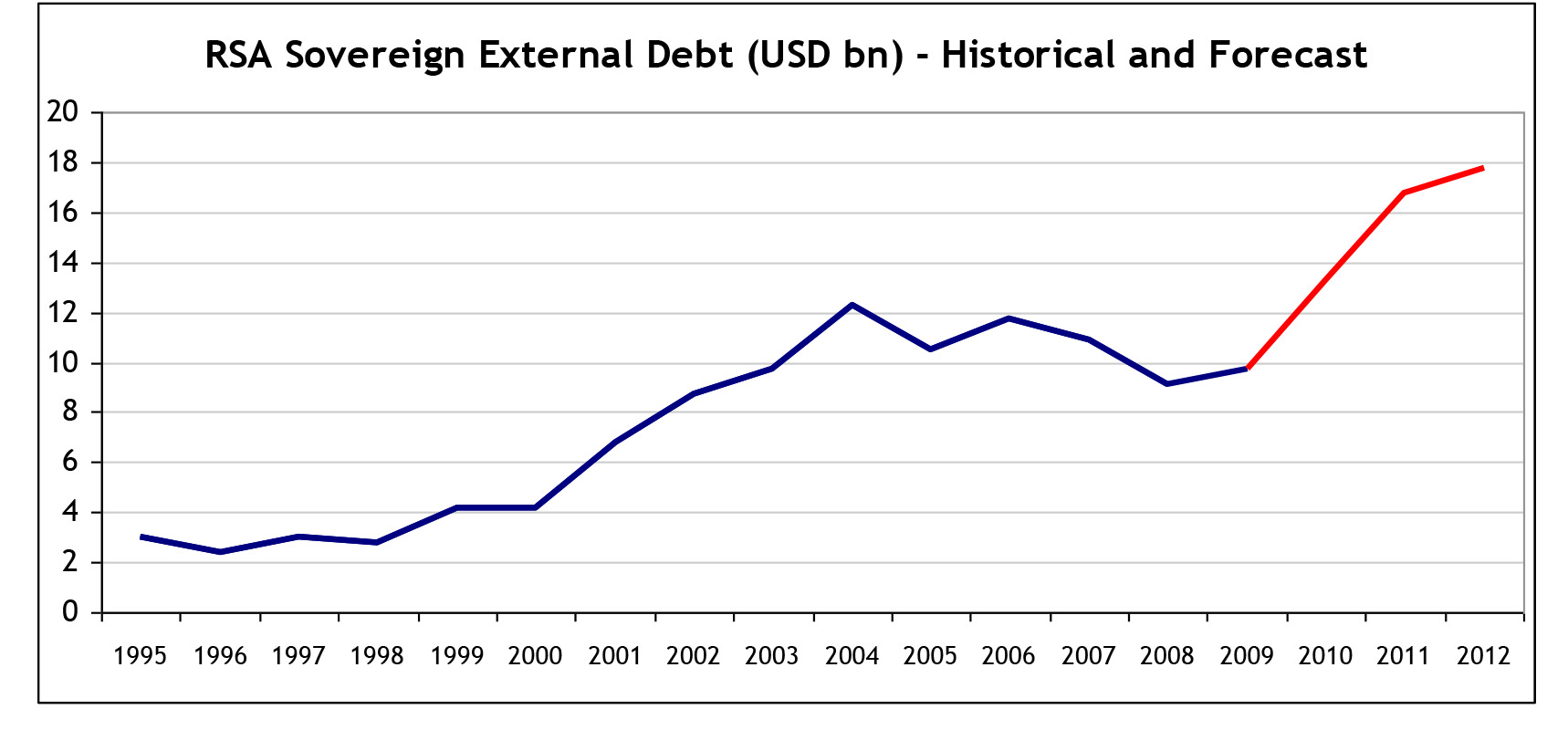

In the recent budget, National Treasury outlined a plan to borrow 1Bn USD per year for the next 3 years. Eskom is set to receive a 5Bn USD loan over the next two years from the World Bank, although it is not certain whether this would be hedged or not. The fact that offshore borrowing, at 15% of foreign borrowing, is relatively small, recently led Treasury director-general Lesetja Kganyago to state that “Our international exposure is far more prudent than any country you would compare us to”. While National Treasury has indeed proved itself to be a very prudent borrower, the rationale for having any foreign borrowing at all is questionable.

Source: JP Morgan, Aeon Investment Management

There has been much research showing the increased risk of a financial crisis associated with foreign borrowing, with the level of foreign currency debt a key determinant of the stability of economic growth, the volatility of capital flows and credit ratings of emerging economies (Eichengreen and Hausmann (2005)). The South African treasury has essentially a Rand revenue stream, and the traditional justification of offshore borrowing on the basis of „diversification of funding? or „lower borrowing cost? does not justify the increased risk. The timing of the offshore borrowing is also poor, as the credit crisis has caused South Africa?s bond yield spreads to widen in the offshore market, and diminished much of the cost advantage. South Africa?s USD and Euro bonds trade at a yields of around 6% to 7%. This is hardly a significant cost saving when measured against the 8% to 8,5% interest rate that treasury would have to pay on local Rand bonds, without any of the associated currency risks.

The final and most valuable argument against foreign borrowing is simply that we don?t need to. South Africa has fully developed capital markets, so there is no reason to go offshore for funds which could be raised here. With the deficit set to increase significantly going forward, the increased borrowing requirement may lead to an increase in government bond yields. However, this would be a reflection of the economic reality, and the benefit of higher yields would accrue largely to local savers, as opposed to foreign funds. Offshore investors are already active in the local market, and are free to buy Rand denominated government bonds and hedge out the currency risk if they think it necessary. With a large local market for South African bonds, there is no need to risk joining the long list of countries that have experienced a financial crisis due to foreign currency borrowing.